No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention

I recently finished No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention, written by Netflix cofounder and CEO Reed Hastings and author/INSEAD professor Erin Meyer. The book describes Netflix’s approach to building high performance and innovation into their culture. I wanted to share my notes and highlights from the book.

I feel compelled to start this post with the typical qualifiers on culture books: Is this account truly representative and accurate? How many different cultures actually exist inside a company as large as Netflix? However, when you read the book and look at the results of the company, you just get the sense they must have tapped into something special as it relates to how they organize and run their company. From DVD shipments to streaming, from licensing content to award-winning original productions, they’ve built a company that figures out a way to delight users, despite a typical resistance to change that often accompanies organizations of their size and scale. For 20 years Netflix has proven they can innovate, pivot, and execute. Something inside their walls is working, so it’s worth paying attention to the principles outlined in the book.

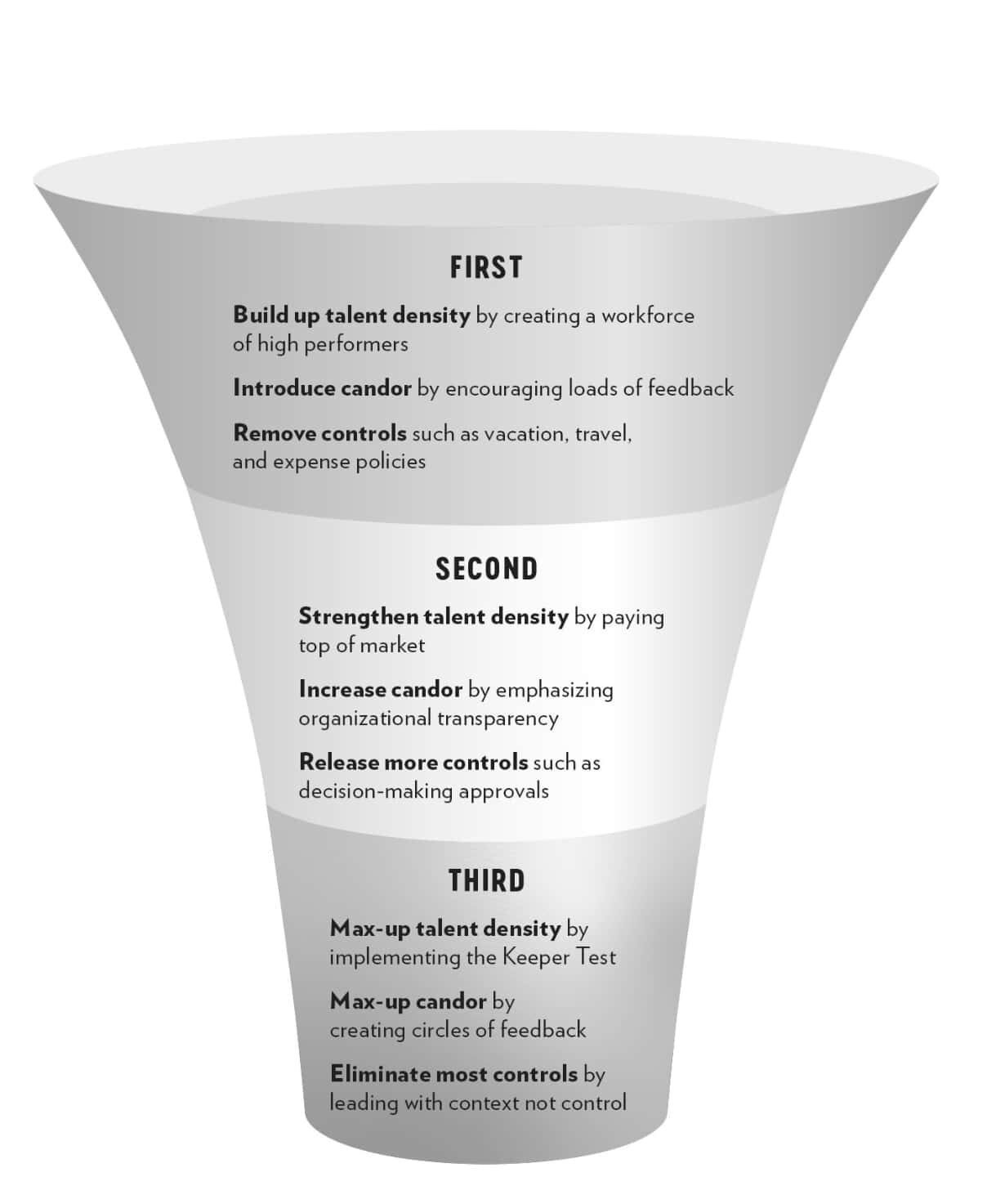

The book recommends a 3 phased approach to building culture, with each phase broken into 3 subcomponents:

Talent Density - Think about this as talent per capita. Does each new hire raise the average talent on the team? CEO Reed reminds employees, “We are a team, not a family. We want the best person at each position.”

Candor - A belief that “frequent feedback magnifies the effectiveness of the team.”

Reducing Controls - “Leading with context encourages original thinking,” and “Don’t seek to please your boss, do what is best for the company.” If leaders provide proper context, employees will feel empowered and make the right decisions.

Reed and Erin outline how you can lay a foundation for each, and then turn up the dial over time.

On talent density:

It’s well known that Netflix aims to pay at the top of the market to ensure they’re recruiting and retaining the best people. “We would rather have one stunning superstar than a couple of average people.” Notice the word stunning. They use it over and over to describe what they’re looking for in each and every hire. If a manager wouldn’t describe a teammate as “stunning,” they thank that teammate for their service and send them home with a generous severance package.

Netflix managers encourage teammates to go out and interview at other companies. Leadership wants everyone at the company to understand their market compensation so that Netflix can match or beat it.

A line stood out to me when Reed was describing how he feels attending meetings at Netflix. “You go into these rooms and you feel like the talent and brain power in the room could generate the office electricity.” What a great description.

The thinking on bonuses and “pay for performance” (earning more for hitting certain goals) compensation stood out. They don’t believe in performance bonuses and variable compensation. There are a few reasons for this: 1) Reed believes that incentive compensation plans don’t provide the necessary flexibility for people to adjust and do what’s best for the business. In his view, setting a goal on one metric creates blind spots. What if the best thing for the business over the next 5 years changes, and moving that previously agreed upon metric is no longer the top priority? Who will catch that? Who will prioritize it? The more people with bonus comp tied to a KPI, the less likely it is for someone to catch a different problem and suggest a shift in focus. 2) He doesn’t buy the fact that dangling money in front of high performers will make them try harder. “High performers naturally want to succeed and will devote all resources towards doing so whether or not they have a bonus hanging in front of their nose." He then references a Duke study from 2008 where they test out bonus compensation for various sets of work. It turns out, if the task was mechanical in nature (effort based), performance bonuses improved results. However, if the job to be done had elements of creativity or cognitive load it actually had a negative effect, leading to poorer performance. The results held true across participant groups in India and the US. I find Reed’s arguments persuasive and compelling.

On candor:

Early in the book they introduce a concept called “belongingness cues.” When we get tough feedback, our body and minds react so negatively (pressure, anxiety, nerves, sweats, etc) because we’re biologically programmed to interpret this feedback as a sign that we may no longer be part of the tribe. As we all know, it’s tough not to feel those things when we receive critical feedback. So, when we do give each other constructive feedback, it’s best to remind the receiver that they still belong to the group. It can be as simple as a pat on the back, an encouraging gesture, or a verbal reminder, “you belong on this team, and I am so glad you are in the role you are in.”

They use a very simple tool for soliciting feedback on the ideas they present to one another. When you propose a new idea, you send along a spreadsheet with 3 columns: 1. Name 2. Score for the idea (-10 being “I think this is a terrible idea” up to +10 being “we must pursue this idea at all costs”) and 3. Reason. It’s a very simple way to organize everyone’s view quickly and help the captain make the decision. I’m definitely going to try this out.

Most of us are familiar with performance reviews (formal written reviews completed annually or bi-annually) and 360s (receiving feedback from peers, managers, and reports). Netflix encourages live 360s. In live 360s, you go to a dinner with your team (ideally 5-7 people) and take turns going around giving each other feedback. In front of the team. They recommend aiming for 25% positive feedback and 75% constructive feedback. Doing it in a group setting forces folks to be thoughtful and kind in the feedback they deliver. Wow, what a sign of a healthy team if you can do this. I’ve done this once before and found it extremely helpful, efficient, and believe it or not, trust building with my peers. I got more from that session than any other written review I’ve received.

On releasing controls and providing context:

Netflix appears to be the gold standard on what you might call “radical transparency.” This section was the most inspiring, and had me doing the most reflection. Quite simply, they want to treat people like adults and give all of the information all of the time, with very few exceptions. As an example, they share financial results with close to 700 members of their extended leadership team before they share with wall street. How do they do it? They treat people like adults. The first slide of the internal deck reads, "You will go to jail if you or someone you know trades on this information." They haven’t had a major leak of this information. They did have one employee leave and take confidential information to a competitor. What did they do? Not change a single thing. They advise you deal with these cases as one offs and avoid making the entire org suffer for it.

Even potential layoffs and reorgs are discussed with a broader team. Reed shares the story of a manager telling a direct report that there is a 50% chance they will lose their job as part of a reorg in the coming months. They want everyone to hear the truth every time, so that employees always feel they can trust what comes from the Execs. This also shows up in their communications when folks are terminated. In their departure emails, managers are told to tell the truth. They say “I parted ways with X” instead of the corporate jargon that typically reads, “John is moving on to his next adventure.” They want to give it to people straight. Every major decision is an opportunity to be transparent and discuss what their expectations are for being part of their high performing team. This sounds intense. Right for some people, wrong for others. There are solid arguments on both sides, but this level of transparency seems worth consideration and debate.

One chapter discusses the importance of vulnerability and admitting mistakes. That part is obvious, but I also learned about the Pratfall Effect. The Pratfall Effect states that your appeal increases or decreases when you admit to making a mistake. If you’re perceived as competent, showing vulnerability and admitting mistakes will increase trust in you. However, if you’re not perceived as competent, trust in you will decrease when you admit a mistake.

A key internal mantra at Netflix is “Don’t seek to please your boss. Seek to do what’s best for the company.” Seems straightforward enough. If you’re going to hire stunning people. you should trust them to make great decisions, so long as you’ve done your part and provided the necessary context. I also want to remember their language when it comes to ensuring team members feel free to fail, which is critical for creative roles where big swings are required. “You are not judged based on the results from one single instance or bet. Your performance is judged on the collective outcome of your bets.”

“We don't need to be aligned on each department's plan, we need to be aligned on where we're all going.” I was fascinated reading about how they approach the Quarterly Business Review (QBRs) -- which they view as the time to give leaders the context they need to make future decisions.

On spending decisions, their guideline is “do what’s in Netflix’s best interest.” They had a false start with an initial guideline of “spend as if it was your own” because they learned that team members have different personal spending habits. The new “do what’s in Netflix’s best interest” has proved successful for them. Their tip to employees -- with every expense, just imagine sitting next to the CEO and VP Finance explaining it. If you can picture doing that, you’re good. If you cannot, something is wrong.

Reed talks about how you can pick up clues on how transparent an org is even by looking at the office setup. He talked about meeting a CEO where his office was down a large hallway with 2 assistants out front. He understand in that moment how transparent (or lack thereof in this case) the company was. This influenced Reed to take a different approach with his office behavior. "I always try to go to the work spot of the person I'm seeing instead of making them come see me." I liked that and want to adopt it.

The book finishes with lessons learned about taking a culture global and tweaks one would need to make to ensure the spirit of the culture stays consistent, while accounting for cultural differences.

These were the concepts that stood out to me as the most thought-provoking. I’d be excited to hear your perspective on them, so reply if you have a reaction to any bullet above. I’ll leave you with Reed’s conclusion to the book (spoiler? does sending the concluding summary of a business book count as a spoiler?) because it captures the overall spirit well.

“In today's information age, in many companies and on many teams, the objective is no longer error prevention and replicability. On the contrary, it's creativity, speed, and agility. In the industrial era, the goal was to minimize variation. But in creative companies today, maximizing variation is more essential. In these situations, the biggest risk isn't making a mistake or losing consistency; it's failing to attract top talent, to invent new products, or to change direction quickly when the environment shifts. Consistency and repeatability are more likely to squash fresh thinking than to bring your company profit. A lot of little mistakes, while sometimes painful, help the organization learn quickly, and are a critical part of the innovation cycle. In these situations, rules and process are no longer the best answer. A symphony isn't what you're going for. Leave the conductor and the sheet music behind. Build a jazz band instead.

Jazz emphasizes individual spontaneity. The musicians know the overall structure of the song but have the freedom to improvise, riffing off one another, creating incredible music.

Of course, you can't just remove the rules and processes, tell your team to be a jazz band, and expect it to be so. Without the right conditions, chaos will ensue. But now, after reading this book, you have a map. Once you begin to hear the music, keep focused. Culture isn't something you can build up and then ignore. At Netflix, we are constantly debating our culture, and expecting it will continually evolve. To build a team that is innovative, fast, and flexible, keep things a little bit loose. Welcome constant change. Operate a little closer toward the edge of chaos. Don't provide a musical score and build a symphonic orchestra. Work on creating those jazz conditions and hire the type of employees who long to be part of an improvisational band. When it all comes together, the music is beautiful.“